Deep Vellum Fall 2020 Preview

In celebration of North Texas Giving Day September 17, we're releasing micro-excerpts of a select number of Fall 2020 titles coming soon from the Deep Vellum catalog.

Support Deep Vellum by giving a gift that will help us amplify the voices of over 22 different novelists, poets, photographers, and children’s books writers over the next year. These literary artists hail from all different backgrounds and heritages, including seven writers from Dallas! Click here to donate and help us pay our writers, translators, and designers, host captivating events, support our staff, and produce amazing books like the ones below. If you're interested in pre-ordering one of the following titles, simply click on the cover image to visit the book's pre-order page.

The Nightgown and Other Poems, by Taisia Kitaiskaia

"Wept All Day, Didn't Know Why"

Saints are those who do not live amongst the people.

When I first met a saint I placed it tenderly between

Two halves of a sandwich and left it to the wolves. Suchly

Did I observe that no animals came to eat it. At last

One deer pawed the sandwich and nibbled the bread.

Some birds came over to hold a slice up to the sky

Like a banner announcing God’s glory. By this time

The saint was unclothed with its face in the dirt.

I felt sorry &

Shut it back into its walnut shell. I whispered sweet

Gospels. I made a proper burial for it on my tongue.

For a saint must die in its own language. Then

I was like, Okay, and drove home

In my imaginary vehicle splattered with bird droppings.

I became small from crying.A pulley system geared

Until it snowed inside of me. Good grief I said. It was time

To bring my hands together over a woman’s body and worship.

Time to turn off all the faucets God had forgotten about.

Long is my journey to all the empty restaurants crammed into a walnut

shell.

Irreversible is my decision to eat the browned defeated apple

On my way to the bathroom. Now nobody knows me. Not even God

Knows me, He who pares his fingernails my whole life long.

Like the saints I will now be stingy with my love &

Pave a road out of myself so it may be traveled by those

Hungry for bread. Night, reckon us back into the original loom.

Braid our hair into the branches so we cannot move,

So we may be happy.

If you see a saint in the road please put it back.

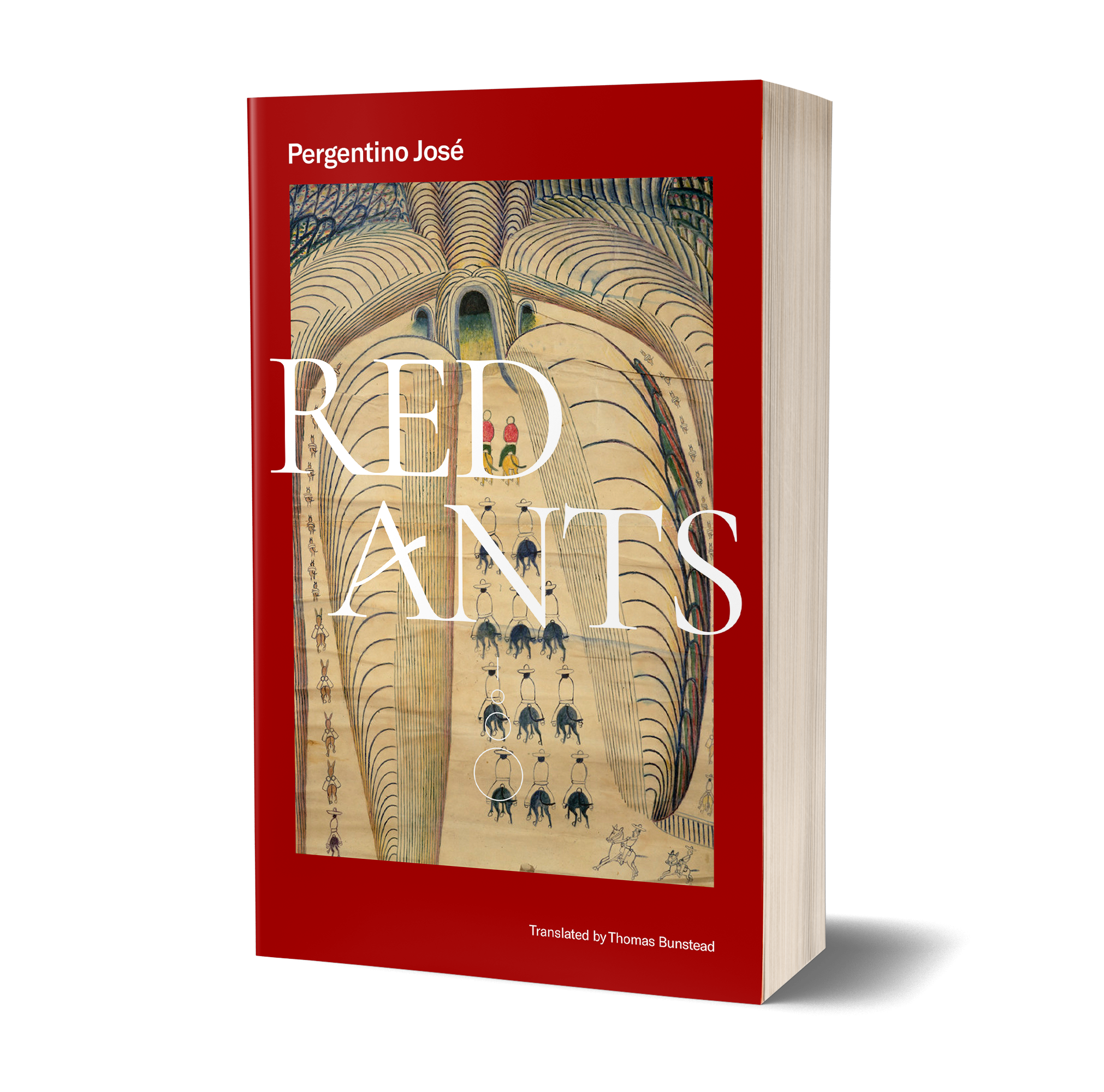

Red Ants, by Pergentino José

from "Prayers":

Night is coming down. Though I can barely make out the younger woman’s fea- tures, she seems wary. In addition to the shawl she wears several white necklaces, giving her a certain elegance. She says, “We never thought Padre Edgardo would rule the city like this. He shut down the two cotton factories, so many people have been cast into poverty, and to top it off we aren’t even allowed to walk the streets at this sort of hour.”

The other woman nods along to the com- plaints. I pretend I have to go, telling them I’m just looking for a friend who lives at the end of the street.

“Just along here,” I say, hoping they might confirm it for me. “Number 56, Calle Padre Edgardo . . .”

“Listen to the radio,” says the older woman. Her tone is that of a mother imploring her children not to go out into the streets while a terrible event is unfolding. Then the other one, who seems more perturbed still, asks, “Can you read?”

I say I can. Their talk is grating on me, I want to get away now. They’re right, it’s risky going out walking, but it’s my choice. The younger woman exclaims: “Read the newspaper! Every day there’s new things. Roads with new names. A new set of people arrested over- night. Buildings seized. People they’re going to deport.”

Then, as I am beginning to despair, the ceremonial sound of bells strikes up in the distance. The women get down on their knees and start exhorting me in trembling voices. “Read the newspaper, young man,” the older woman says. “Do it for Padre Edgardo.” And she takes a newspaper from her bag and hands it to me before the pair turn and hurry away, no goodbye—as though the Sentinels were training their sights on them already.

At the Lucky Hand, aka The Sixty-Nine Drawers, by Goran Petrović

Adam Lozanić remained to stare at the calendar, which was tacked askew to the inner side of the door that had just been closed. A square pencil mark framed the twentieth of November, a Monday. The man’s wife would wait for him?! But where?! And what could all this mean, except that the mysterious man had found out his little secret?! He shuddered. Anyway, he was certain he had never revealed it to anyone. Beginning a year ago, from time to time it seemed to him that when reading he met other readers inside the given text. And from time to time, only now and then but more and more vividly, he would later recall those other, mostly unknown people who had been reading the same book at the same time as he. He remembered some of the details as if he had really lived them. Lived them with all his senses. Naturally, he had never confided this to anyone. They would have thought him mad. Or at best a little unhinged. Truth be told, when he seriously considered all these extraordinary matters, he himself came to the conclusion that he was teetering dangerously on the very brink of an unsound mind. Or did it all appear to him thus from too much literature and too little life?!

Now that he had remembered the reading, it was time to engage in that by means of which, at least for the present, he still earned his livelihood. New texts were waiting, and he sharpened a pencil and got down to work.

Dispatches from the Republic of Letters: 50 Years of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, edited by Daniel Simon

from "Josef Škvorecký, the Literary King," by Arnošt Lustig

Literature is, unfortunately or fortunately, connected in our age with his- tory, politics, philosophy, with everything in which man is involved. During Škvorecký’s lifetime so many things have happened, and so many happened so close. A writer who comes from our country—which was given in appease- ment by Chamberlain to Hitler in 1938, a country where children were lis- tening to the news of how Mussolini was bravely defeating the barefooted Ethiopians with his tanks and how the Spanish Republic was lost because of Western indifference—the writer is up to his neck in politics. A writer in that part of the world has a taste of history involving human fate, like those chil- dren who are ill with a sickness that comes to them from their mothers’ breasts without anyone’s knowing it; years afterward, when they know, it is too late for a cure.

Why am I saying this? Because to listen to a writer means to know and maybe to be able to prevent. Kafka saw the penal colonies before they covered Europe like a plague. To recognize a writer sometimes takes a lifetime and sometimes centuries. Some writers, never discovered, disappear in the abyss of the forgotten, as does their work—sometimes in an abyss, sometimes in flames, sometimes in silence. The lives and works of some writers disappear so completely, it is as if they had never been alive, had never written. That is why recognition of a writer is so important—just like the conquest of a new continent, the finding of a secret treasure or the discovery of a new star.

There is an old proverb which states that a king who is not accepted by his people is not yet a king. Today Josef Škvorecký, the voice of Czech literature at home as in exile, opposed by the authorities in his native land and welcomed and loved by people abroad, is a king. Kings of literary realms are, contrary to other rulers, not dangerous to living creatures. They are threats only to the minds of those who claim the ownership of people as if it were the ownership of goods, those who—as in the dark times of history—are today trading and selling people for money, goods and political gain, especially writers. Literary kings do not kill their enemies; they do not kill people at all, with the exception of themselves.

Literary kings are, in comparison with the real kings of the world, more gentle, more silent, more generous, in spite of the fact that literary kings, like all kings, must fight from time to time. Josef Škvorecký is not one of those people who, by claiming that they are fighting the last battle of man, are ready to bury not only man but his world as well. It is a beautiful privilege to say that Josef Škvorecký is a winner today, and to know that he wins in the name of, and for, all of us. It must be marvelous to be a literary king.